NEW YORK

Kazuko Miyamoto

Works 1990 - 2018

October 18 - December 2, 2018

KAZUKO MIYAMOTO has lived and worked in New York City since 1964. She was born in Tokyo in 1942 where she studied art at the Gendai Bijutsu Kenkyujo (Contemporary Art Research Studio). She moved to New York in 1964 and attended The Arts Student League of New York (1964–1968).

Zürcher Gallery has published a catalog accompanying this exhibition: Kazuko Miyamoto in New York City: Works from 1964 to the Present. Available for purchase at Zürcher Gallery, NY.

We are thrilled to present historical and significant work by Miyamoto from the late 1990s until 2018, which show the wide range of her enduring artistic practice such as her performance work. This is Miyamoto’s second solo exhibition at Zürcher Gallery in New York concurent with her inclusion the 50th Anniversary exhibition at Paula Cooper Gallery, NY and the National Museum of Art, Singapore’s exhibition, “Minimalism. Space. Light. Object.”

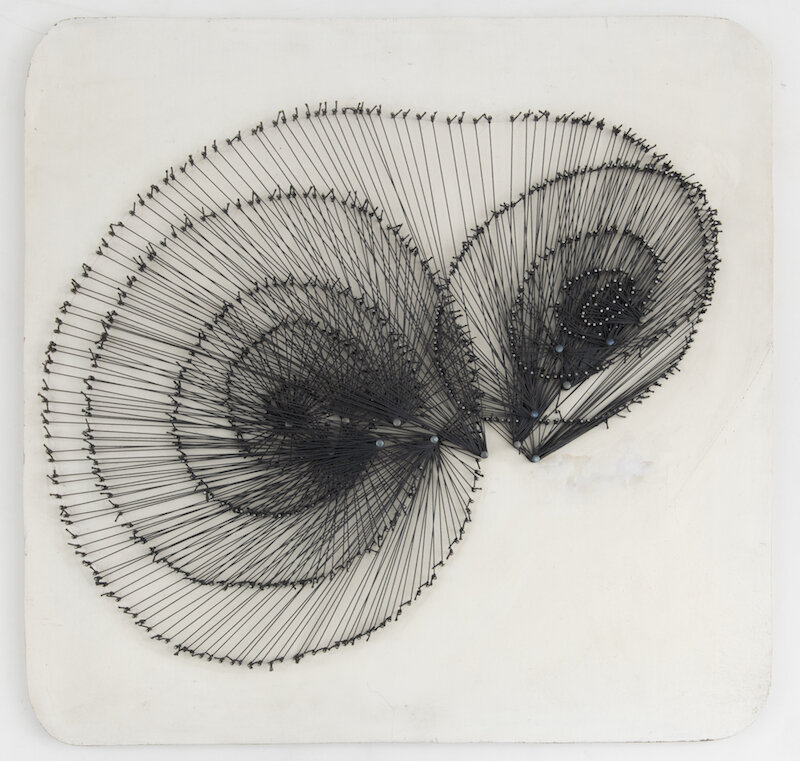

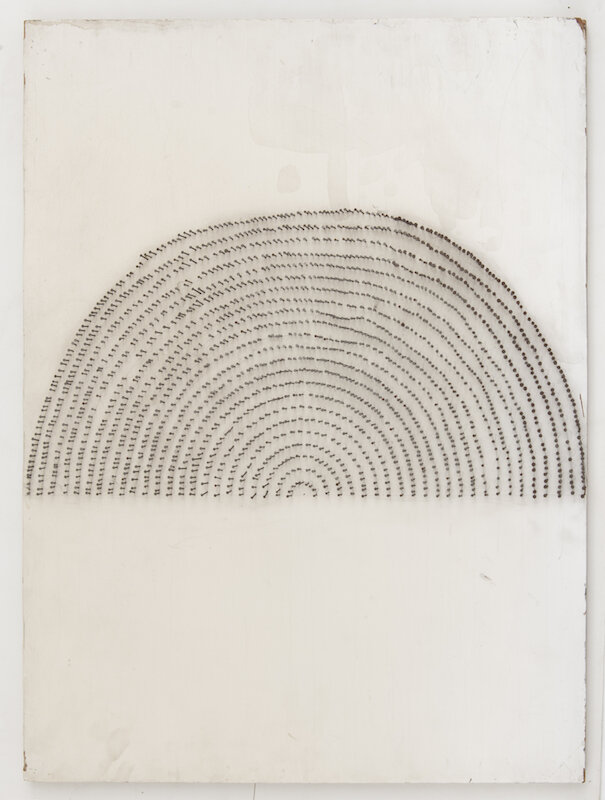

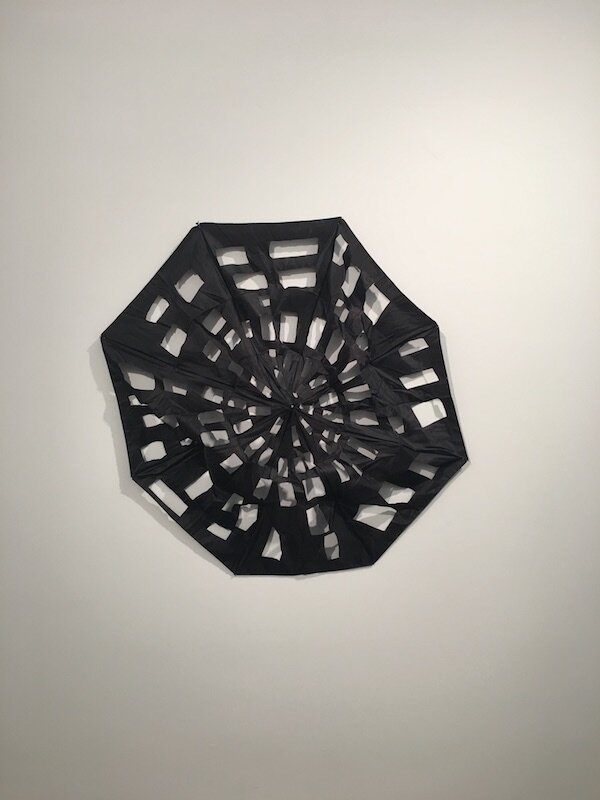

In the 70s, Miyamoto was making installation, paintings and drawings, using a playful minimalist vocabulary. From the ‘80s, the tendency toward a cross-over between art and life became urgent, prompting the artist to explore, more and more frequently, the performance practice through which she addresses issues related to her identity and her individual memory, ethnicity, and gender. The shift from minimalist instances to issues of identity took place in a gradual and not absolute manner, so that both orientations still continue to exist in her artistic practice. Early in her career, Miyamoto worked as Sol Lewitt’s assistant and became interested in minimalist and post minimalist attitudes. In her work, she explores geometry, female forms of craft, body relationships, and quotidian materials. She uses fallible materials to poke fun at the machismo associated with Minimalism’s “fore fathers”.

Excerpt from “Life Ends, Dreams No”, Essay by Valentina Gioia-Levy from The Pink Gaze:

“The concept of body-memory proposed by Jerzy Grotowsky (1933-1999), who regarded the body as a sort of archive for the personal and cultural experiences of the performer, is extremely useful in understanding the true nature of Miyamoto’s performance. Whether they are sequences of simple actions from everyday life (such as climbing a ladder, wearing a traditional dress, walking, sitting in the snow), or whether they are choreographies or a mise en scene, Miyamoto’s performances always imply the presence of a body-receptacle which retains and stores cultural or lived experiences, releasing them in the form of interactions with the outside. In Miyamoto’s performative actions there is always a character of unpredictability linked not only to the intinctiveness of the acts themselves but also to human mechanisms put in place by the artist. The human factor is an integral part of her performative language, and in some cases it works as a device for ensuring a most effective mise en scène. Prioritizing the outcome of the performance over its process, Miyamoto traces the plot of an action that will take its final shape only in the moment when all the single events previously put in place come to fruition.

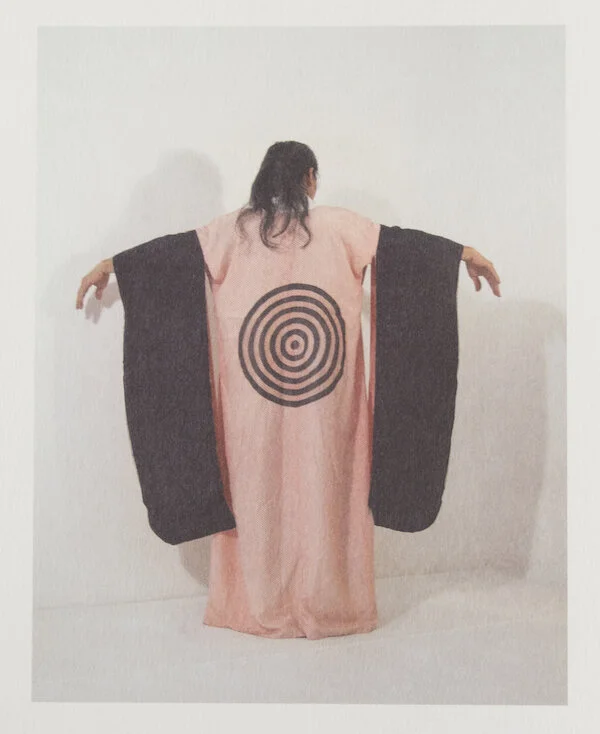

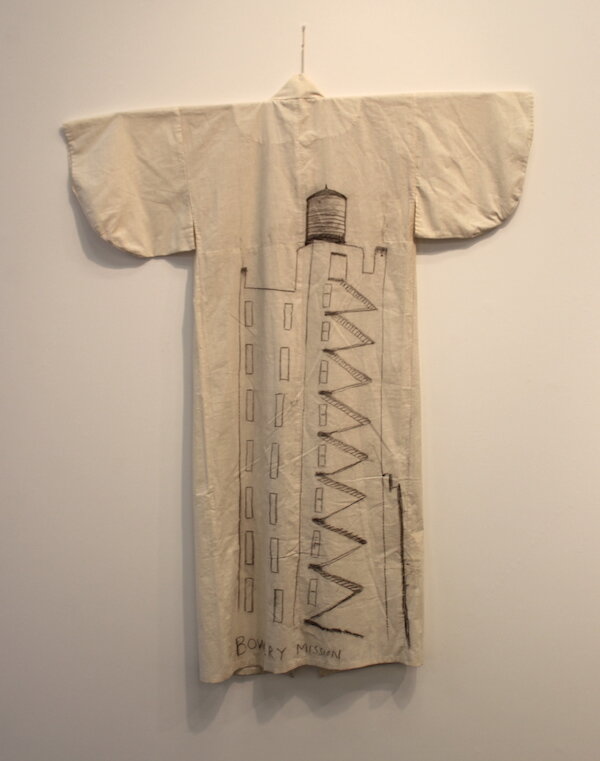

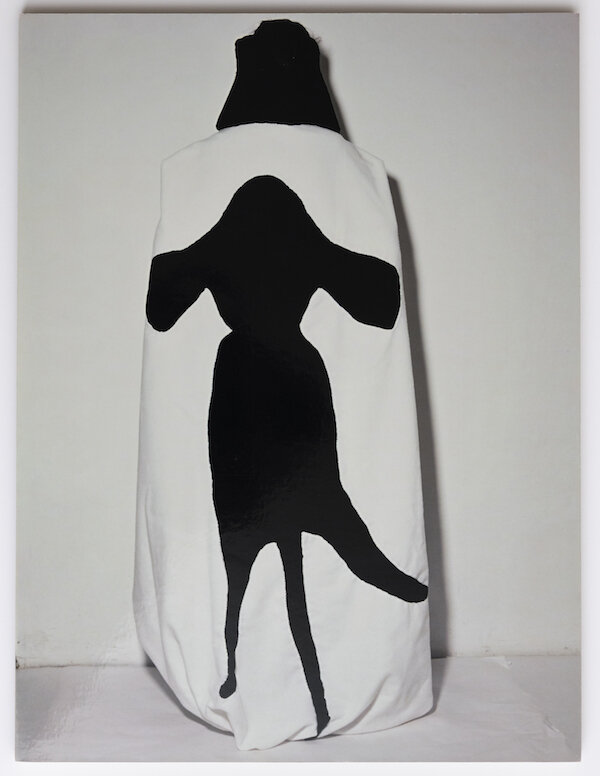

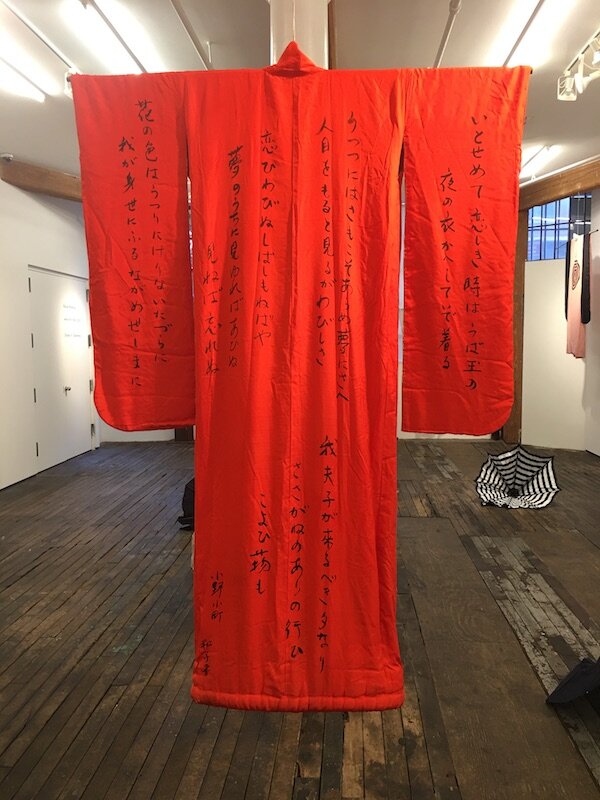

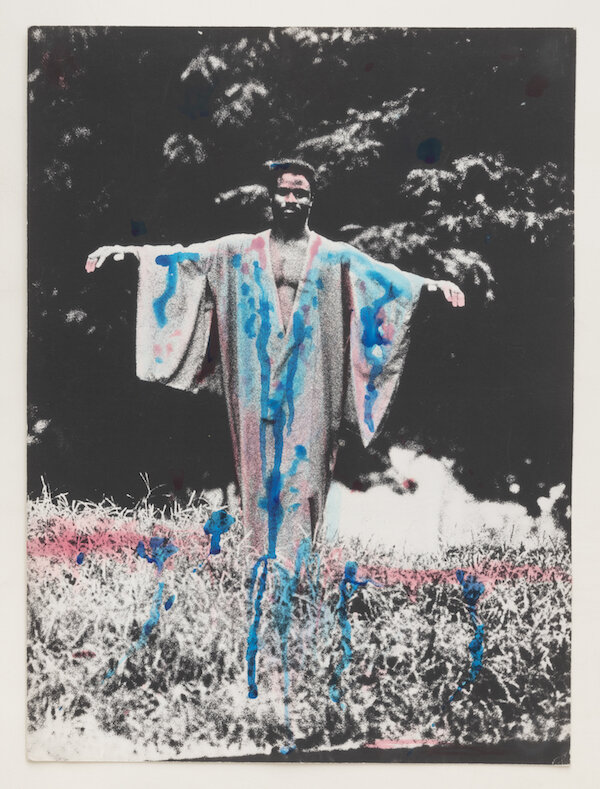

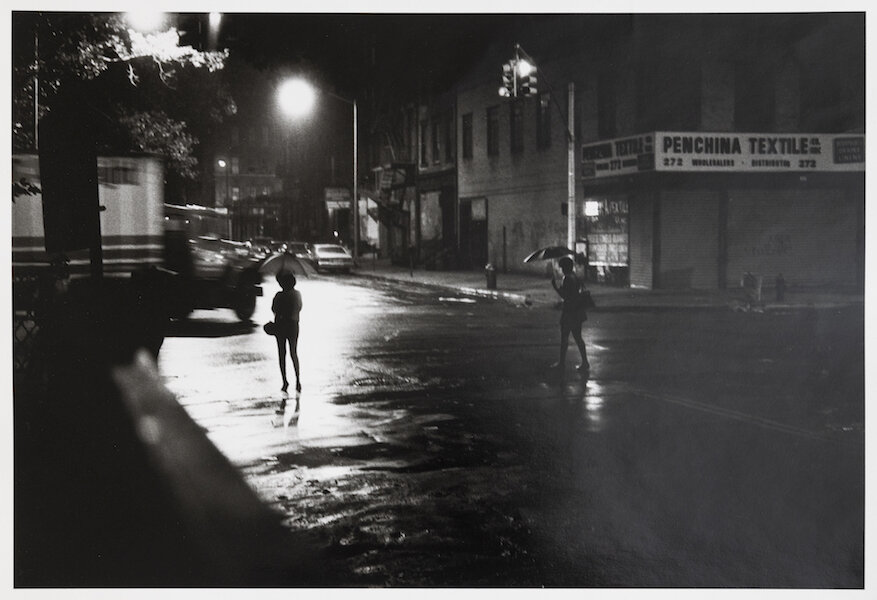

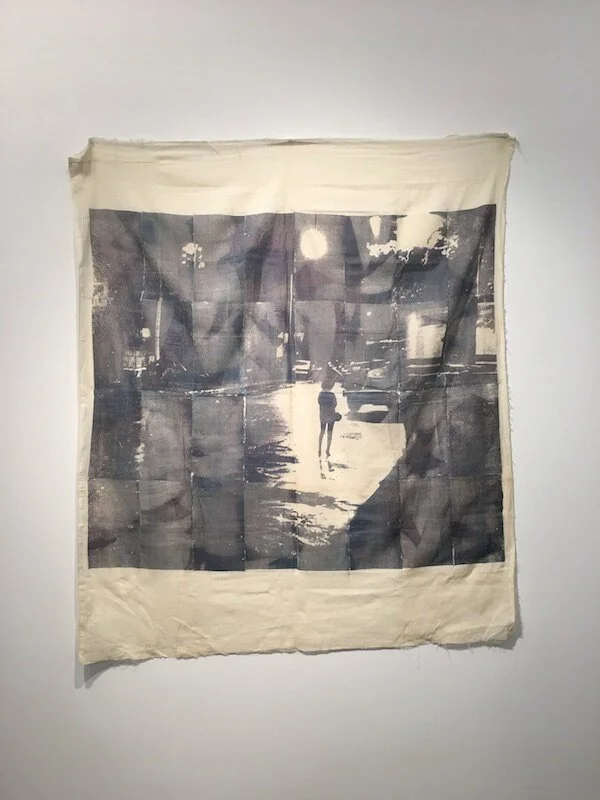

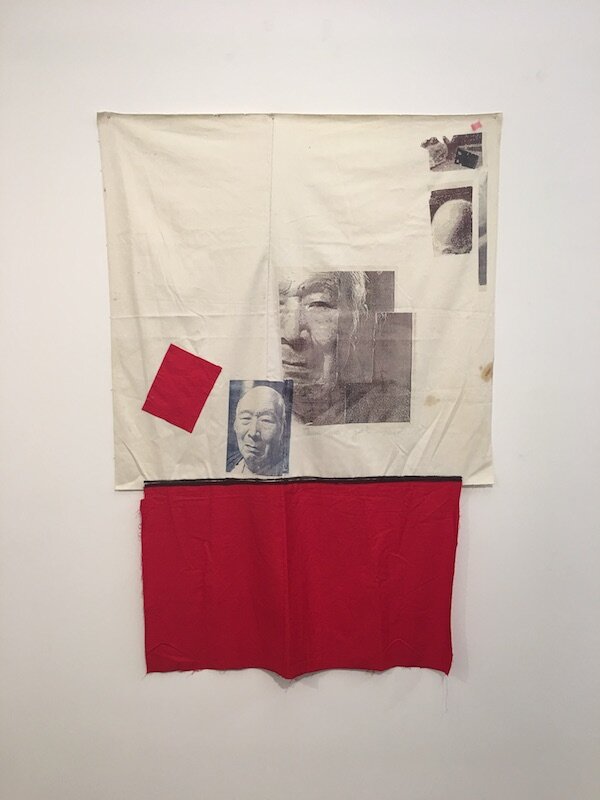

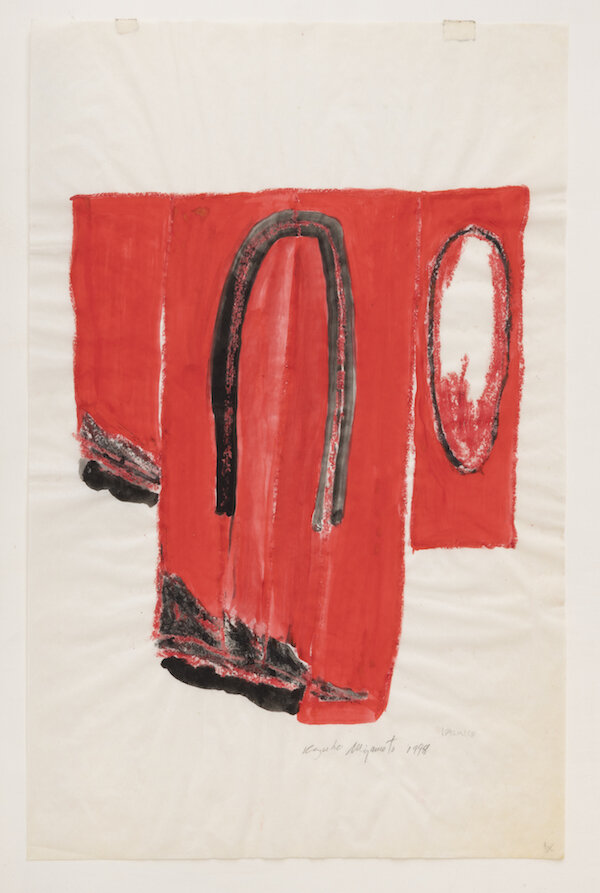

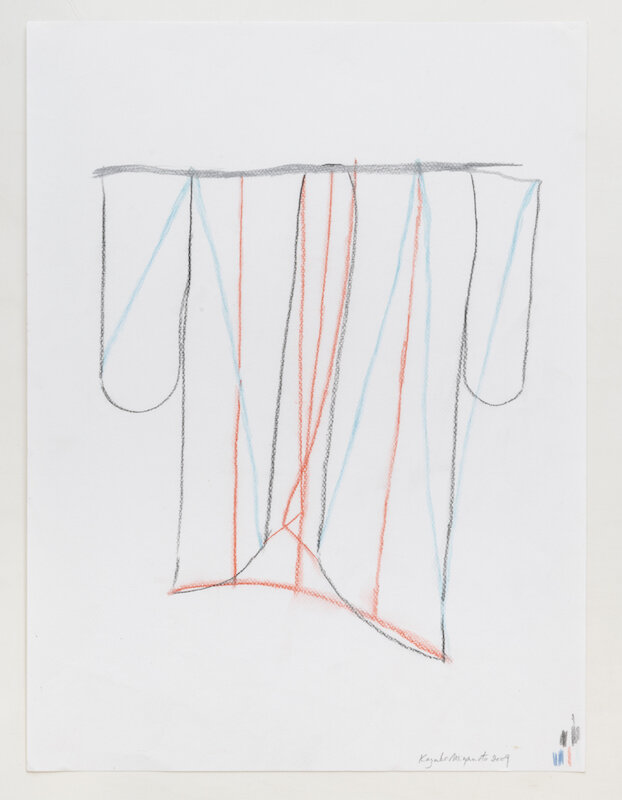

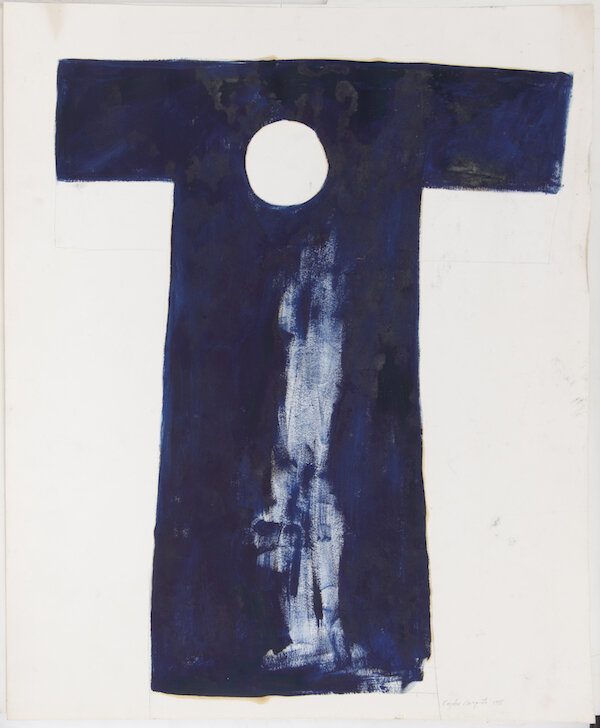

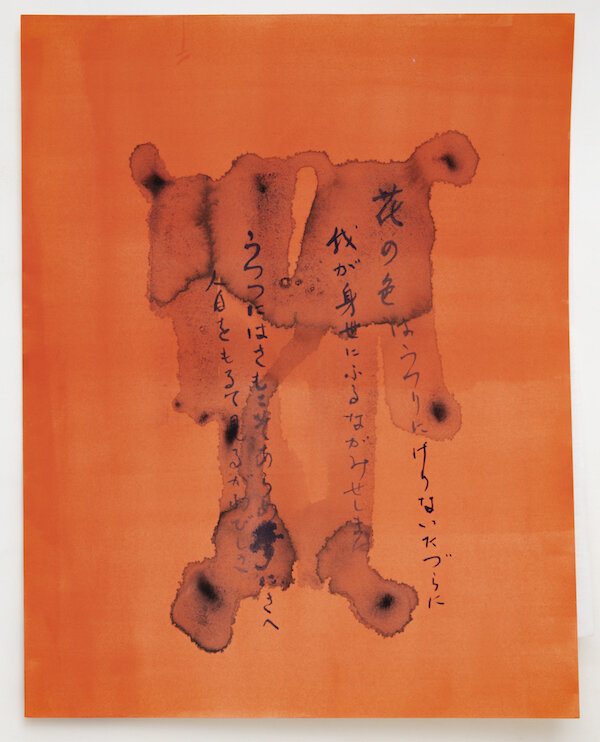

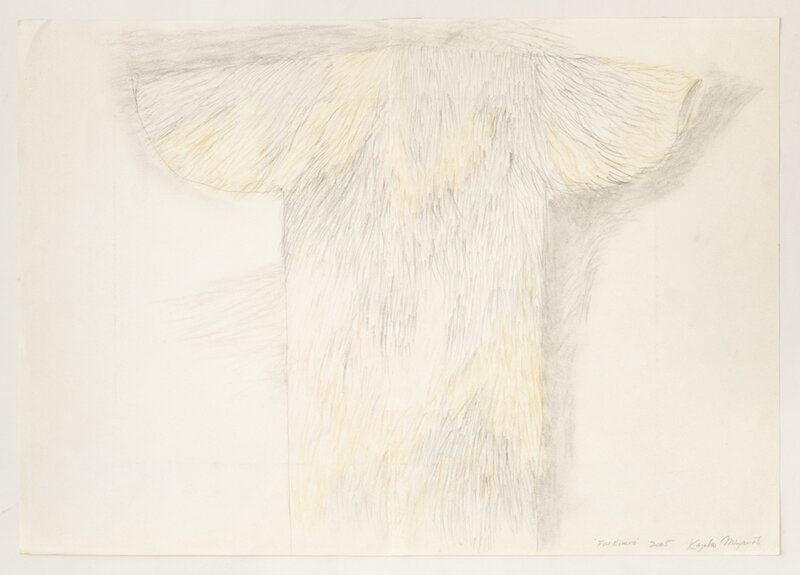

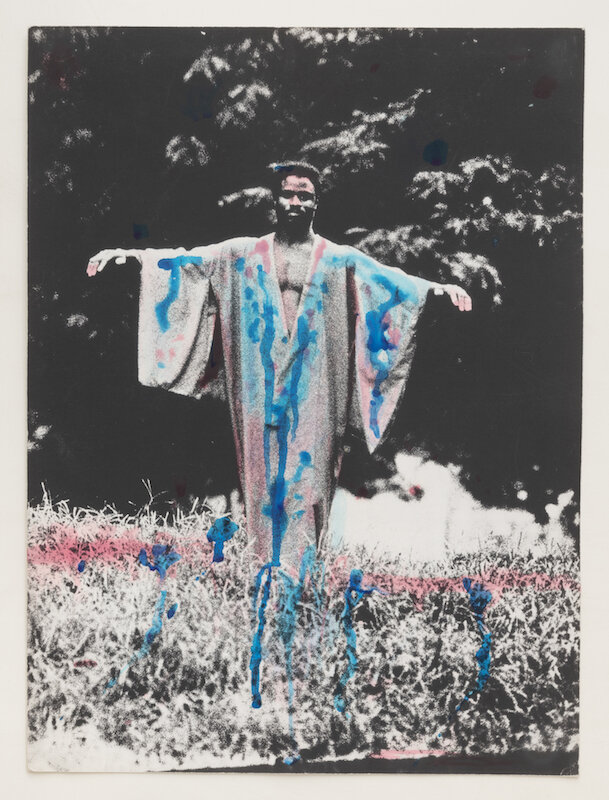

The performative language of Miyamoto combines visual elements, gestures, sounds and symbols coming from traditional Japanese culture as well as the multi-ethnic subculture of the Lower East Side of Manhattan in the same performance. The artist makes full use of the codes of contemporary art practice as well as those of traditional performative practice, overlapping and synthesizing signs and meanings. In Matador performance Miyamoto, with long flowing hair, wearing a kimono and a photo of her dead father as a mask and using hand-made ropes like a shimenawa, which are knotted strings of paper fiber used in Shinto rituals to mark the sacred space, drew upon the Kagura as a form of dance-theater, creating a polysemous expressive language, which was at points cryptic and difficult to decode for those who are not familiar with traditional Japanese performing arts. She created a self-referential language that does not have as its goal the communication of a message, but the sharing of a state of being and the finding of a lost identity. Finally, in the context of choreographic performance, the use of everyday objects as props is essential to Miyamoto’s work: objects such as clothing and accessories such as dresses, kimonos, obi, colorful umbrellas, all kinds of objects intimately connected with her history and her daily life, such as a plant, a mat or an old picture of her father. Miyamoto mostly uses such objects as instruments for exploring the expressive possibilities of her body relation to the exhibition space, delimiting the scenic area or simply attracting the viewer’s attention to an exact point. In her performative language objects also serve as tools for redefining her individual, social and cultural identity.1 With few exceptions, as in the Waiting for Carnival performance where she wore the clothes of a homeless person, or in Kazuko in the Snow, a performance in 1998, where she layed down in the snow, wrapped in a fur coat, Miyamoto chooses to work primarily with the kimono. As a traditional dress, the kimono carries with itself strong cultural connotations. It is a universally recognized symbol of Japan, Miyamoto’s home country and the artist chose this dress precisely because of its semantic value. The Kimono Works are created to be worn, almost like stage costumes and are often bound to a memory or a life experience. Miyamoto tends to provide details about these remembrances adding specific sub-titles, or small additional notes. The specific works Bought in Kyoto or Donated by my Father reveal ¬the perception of the object as a product of the artist’s life, an expression of Erlebnis, which seems to have become an integral part of the work. Miyamoto uses the kimono to represent vestiges of her memory. For Miyamoto the dress becomes an instrument which brings a sentimental and intimate value to light within her work. In Standing Man (1984), for example, the artist printed an old photograph taken secretly of her naked father, on a lightweight silk kimono. In Plant Kimono (1990), she reproduced the image of a plant in her apartment, an apparently insignificant subject, yet the plant has been a silent witness to all her most intimate moments. In Ono no Komachi (2004), the artist transcribes love poems of the poet Ono no Komachi (active around the middle of the ninth century) on a ceremonial kimono, given to her by her father.2 In Women on a Step-ladder (1987), the artist reproduced the image of one of her impromptu performances where she sat naked on a ladder; while in Black Kimono, she stuck black and white photographs of her performance Kazuko in the Snow (1998) on a short Yukata, a lightweight silk blouse.

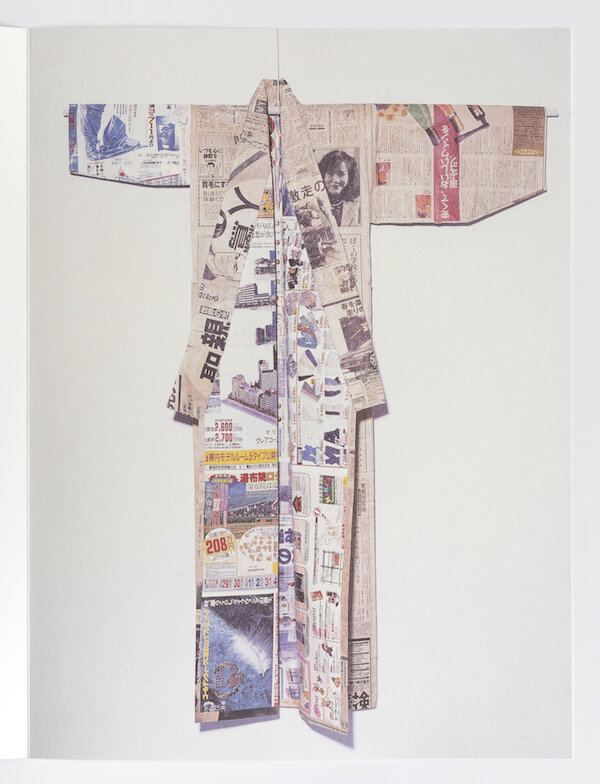

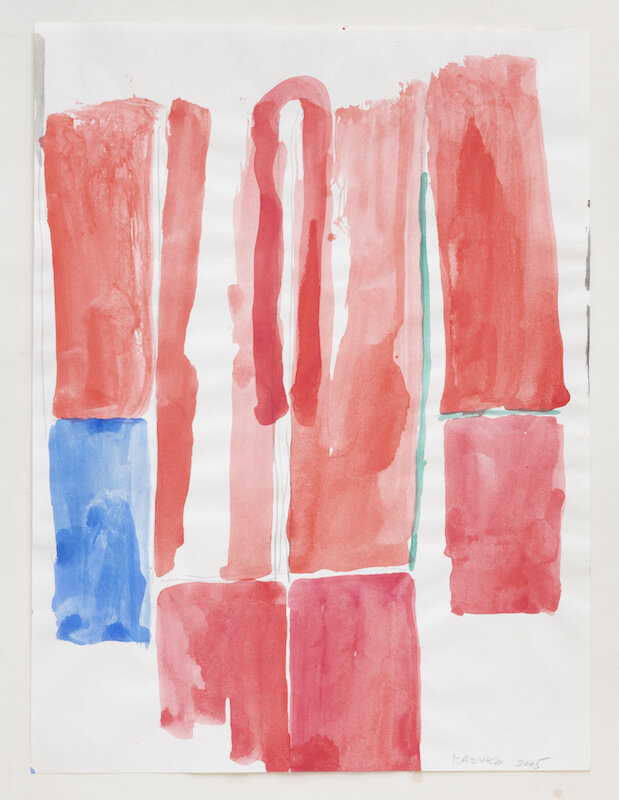

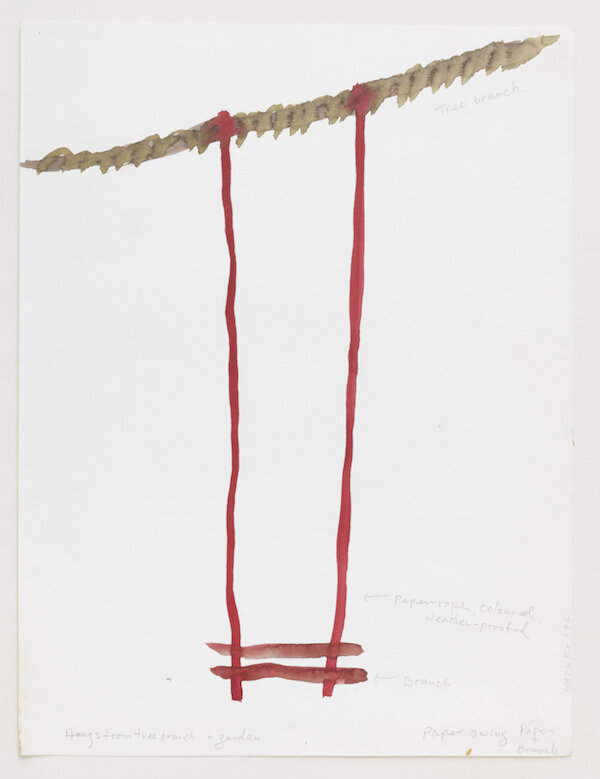

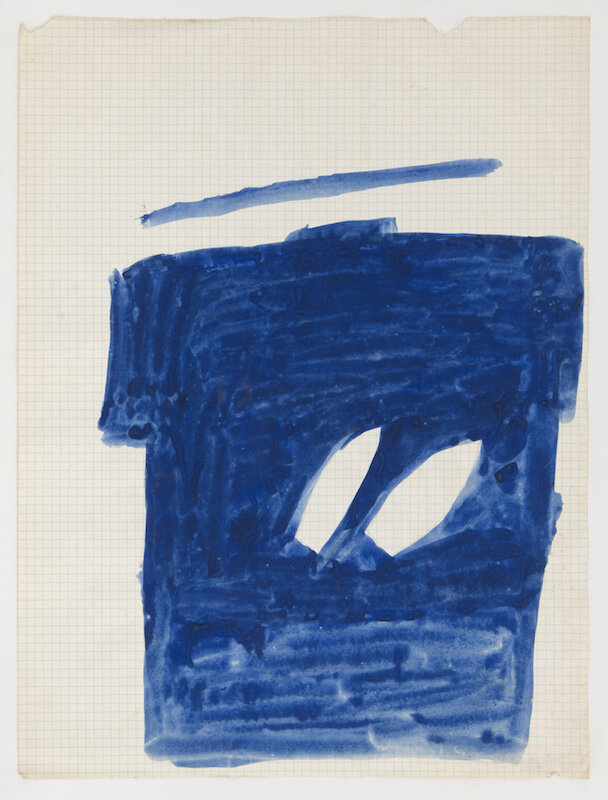

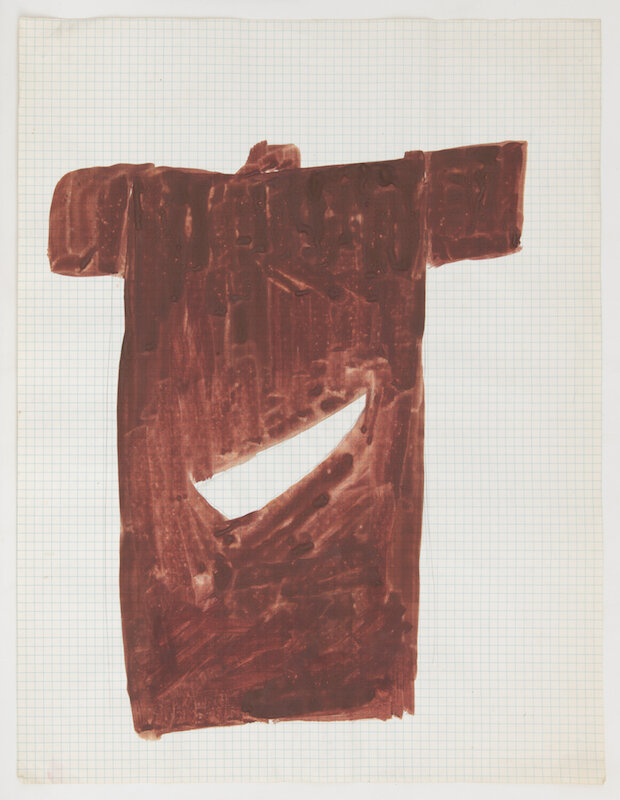

In other cases, some of the kimono works appear to distance themselves from narcissistic and identity-oriented issues, moving toward a focus on process, based on attention to material, to the process of realization and to the recovery of the form, in the sense of the archetype. In Paper Kimono, for example, Miyamoto uses newspaper clippings to create a sort of Japanese kimono sculpture. The Kimono Drawings (right) are works on paper made between the ‘80s and the 2000s, in which Miyamoto alternates the use of pencil, watercolors and charcoal. Closely related to the kimono works, the drawings allow a regression to the moment that precedes the artwork, corresponding to a planning stage and a meditative and exploratory phase, a place for fantasies and possibilities. As well as kimono works, the drawings are a kind of diary and also the result of the overcoming process of the boundary between art and life which the artist started in the 80s. Just as with her performances, in the Kimono Drawings elements such as instinctive gesture, non-premeditation and randomness prevail. Free from minimalist and geometric structures, her drawing style seems to regain its virginity and express itself with a childish spontaneity and a naturalness which shows the authenticity of the artist’s state of mind.”

Notes

1. Documented since the XVII century, the Kagura was a shamanic ritual in which the officiant, often a priestess, called on earth a Kami, which according to Shinto are the spirits who animate nature or even the souls of the ancestors. This term now refers to various forms of traditional dance practiced throughout Japan which are characterizd by slow steps, rigidity of the body, amplification of gestures, use of maks and ritual objects which in ancient times were meant to invoke the gods. Benito ORTOLANI, Il teatro giapponese. Dal rituale sciamanico all scena contemporanea. (edited by Maria Pia D’ORAZI) Bulzoni Publisher, Rome 1998. 2. KATÔ Shûichi (edited by Adriana Boscaro). Storia della letteratura giaponese dale origini al XVI secolo. Marsilio Editori. Venezia, 1987.

KAZUKO MIYAMOTO has been the recipient of Federico II: Premio Internazionale di Pittura; Italy in 2003, the Francis J. Greenburger Foundation Award in 2003, and the National Endowment for the Arts, CAPS in 1979 & 1980.

Select Public Collections include: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Museum of Modern Art, Print Collection, NYC, Wadsworth Antheneum, Princeton University Art Museum, National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, Japan, Neue Gallerie der Stadt, Linz, Austria, Lentos Art Museum, Linz, Austria.

Select Private Collections include: Sol LeWitt Collection, David Hammons, Nancy Spero and Leon Golub, Werner Kramarsky, Heide and Hanna Streick, Tadanori Yotsuda, Marilena Bonomo.